There are plenty of good books on hill craft, and we don't intend to compete with them here, but there are one or two tips on navigation that we could pass on from our experiences. First you are crazy if you go into these hills without

(b) an Ordnance Survey map of the area

(c) the ability to use map and compass together

We tried a purpose made mapholder - a plastic wallet on a cord that goes round your neck and hangs down in front of your chest. So first you try this outside your jacket and the wind keeps catching it and skelping you in the face with it. Then you try it inside your jacket and bang goes the breathability of the jacket and you simply cook inside.

So we recommend a 10p photocopy instead.

This however is no substitute for having a proper map in the first place. You will want to know what is all around you beyond the reaches of your photocopy. You will probably pour over it both while you're planning your route and after you have been on it - to build the picture you will carry in your head of the area in the future. We find that the "Landranger" maps are clearer to read than the "Pathfinder" (the old style 1:25,000 series - not shown above because we never used them because they were so difficult to read) or "Explorer" series. It is easier to see the form of the hills in the Landrangers. The Harveys map is excellent in this respect too, plus it shows the fire breaks in the forest which can be invaluable at times.

The maps used throughout this site are hand drawn - based mainly on the Ordnance Survey "Landranger" series. While they give a reasonably accurate picture of the general shape of the hills etc., they are not intended as main line navigational tools for use on the hill. The much greater accuracy and detail of a proper Ordnance Survey or Harvey map is needed if you are to risk life and limb in poor visibility. Even these are no use to you without a compass, and the knowledge of how to use it in conjuction with a map. Like most people who go on the hill we are very independent spirits and we have a relaxed attitude about most things in life - but poor navigation is not something you can be relaxed about and you can soon come to be very dependent on others that way.

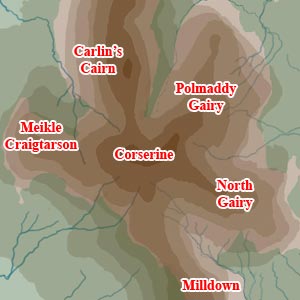

With the top of Corserine being so flat and featureless

you can very easily get disorientated in mist. One great shoulder runs

west and two run east off the main ridge so you have five ways off. Now

if you spend any length of time at the trig point talking and wandering

about, it is dead easy to lose the sense of the direction you came in

from and yet still be convinced that you know it fine, and so you set

off on what you are sure is the right direction until you suddenly realise,

if you're lucky, that the terrain is not doing what you expect it to do

according to the map. Part of the problem here is that there are only

two points of reference, the trig point and you, and no other visible

reference which keeps in your mind your relationship to the trig as you

first encountered it - two points don't make a triangle, and without that

third reference you can be anywhere 360 degrees around the trig and every

view looks the same (ie. flat stony ground disappearing into mist).

You could easily end up going down one of the shoulders by mistake - not

necessarily dangerous, but adding hours onto your day. Navigation in poor

visibility depends on moving from one recognizable feature or landmark

to another. When you locate each feature you know exactly where you are

on the map and you just take compass bearings from the map for the next

feature along the route. Trouble arises when for some kind of weird macho

reason you think you don't need the compass because you believe you know

instinctively which direction is which.

| Site Homepage |